Mari Mari Cultural Village in Sabah, Borneo

Seeing as I permanently marked myself with a Bornean tribal tattoo before fully understanding what it meant, best I go directly to the source. Ass backwards is how I roll.

So, off to Mari Mari Cultural Village—a living history museum showcasing the traditions and customs of Borneo’s indigenous tribes. Eddie, my guide, picks me up early and gives me a rundown of the massive mountain looming in the distance.

Mount Kinabalu is ever-present in Kota Kinabalu, the capital of Sabah, where I’m currently staying. There are plenty of tours offering a three-night, two-day climb, but I found out too late—so I admire it from afar. Bummer. A good excuse to come back.

Forty minutes later, we arrive and meet the Australian couple who make up our tour. We wait our turn to do the walkabout, as several groups are already lined up, ready for action. Groggy from my 8 a.m. wake-up, I’m in no mood for shit shat—not that any comprehensible words are formulating. My inability to function before noon is well documented.

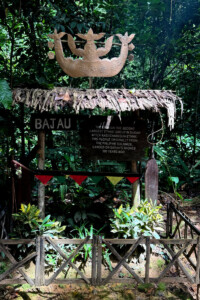

Eddie explains we’ll be visiting authentic huts built by the ancestors of the Dusun, Rungus, Lundayeh, Bajau, and Murut tribes, along with daily rituals recreated by direct descendants. A large majority of the activities are interactive.

Interactive… pretty nifty.

Our first stop is the Dusun—people of the land, skilled farmers, weavers, and rice cultivators, and the largest UNESCO-documented tribe in Sabah. Their language is still spoken today.

Upon entry into their hut, we’re offered lihing, a sweet rice wine served on special occasions. This is my kind of interactive. Albeit, to really taste the stuff, four Dixie cups are required. Making our way to the living quarters, Eddie points to a room elevated above the rest—reserved for the young female in the family, accessible only by ladder.

“At bedtime, the father removes the ladder,” he says.

I offer, “So she can’t sneak out at night?”

“No,” Eddie says. “So no random fellow can get in and snatch her away.”

Okay, well… either scenario applies.

In the kitchen area, we’re given chicken cooked linapak style—wrapped in banana leaves, ginger added, tucked into hollowed bamboo, and cooked over a wood fire. Looks pretty straightforward, but I’d no doubt burn the house down.

Yum yum oh yum is really all I can say.

On our way out, we’re offered yet another type of wine. Cooking is wasted on me; wine making makes more sense. Gotta love these people. Understandable why I feel so embraced by the Sabah community. Tribal instinct, perhaps?

Next up: the Rungus—known for their longhouses and intricate beadwork. Communal living: multiple families under one roof, built from bamboo and palm fronds.

Rungus longhouses sit three to five feet off the ground, with outward-sloping walls. Eddie calls the sloping walls “recliners.”

Outside, we encounter a display showing their honey production.

“This honey is attracting a ton of flies,” I say, swatting at my face.

“Those are the bees,” Eddie explains. “Stingless bees.”

I’m like… WTF. Stingless bees? What will they think of next?

The honey is watery. No violence involved. What did I expect?

We head to the Lundayeh hut. Traditionally hunters, fishermen, and agriculturists, they’re known for hospitality, rope making, and bark clothing. I’m fascinated by their burial ritual: placing the body in an urn, hanging it from a tree, then years later collecting the bones and burying them in a ceramic vase.

I suppose it’s akin to turning forty and becoming inexplicably obsessed with lawn sod.

Outside the hut sits a guardian marker shaped like a crocodile—saltwater crocodiles, that is. This thing is ginormous.

“OMG, are crocs really that big?” I ask.

“Bigger,” Eddie says, turning to the Aussies. “These two see them all the time.”

“For reals?” I ask.

“They can get up to six meters,” Denise says—about twenty feet, she translates.

W. T. F. OK now I’m wide awake. Conversation flows freely at this point. The Aussies are from Perth and are seasoned travelers. When John was a young kangaroo he did the US road 66 route. They are extremely personable with an easy going sense of humor. I’m thoroughly enjoying their company.

Next up: the Bajau tribe, known as the “Cowboys of the East.” They also live in longhouses, but their horses are stabled underneath. By far the most colorful of the five tribes, they take celebrations to another level.

The Aussies and I laugh it up trying on wedding headdresses. Realizing I’m single, Denise insists I wear the gold wedding headpiece. She and John get goofy, yukking it up in the matrimonial section.

It’s obvious these two have a lot of fun together. I’ve overheard their humorous banter and laughed along numerous times.

While not specifically addressed at Mari Mari, there’s another faction of the Bajau known as the Sea Gypsies. Eddie explains they live in houseboats or stilt homes and can hold their breath for up to thirteen minutes at depths of around two hundred feet—thanks to evolution giving them larger spleens for oxygenated blood storage. Crazy. For real.

And then… this is it. Here is where it all comes to a head—the final hut.

The Murut tribe, the last of Sabah’s ethnic groups to renounce headhunting. The hedonist in me is all aflutter.

In the holding hut—at least, that’s what I’d guess you’d call it—are numerous artifacts depicting tribal symbols, assorted skulls, and a variety of tapping tattoo instruments. Eddie shows me a thorny branch used for tapping a traditionally earned tattoo onto a warrior’s body.

I’d arrived at Orangutan Tattoo Studio headless, limiting what tribal tattoos I could traditionally, ethically, or legally etch upon my body. Cliph basically told me it was a woman’s flower of protection or nothing. That’s cool. No way I could carry off a heavy-duty “I chopped off a dude’s head” tat anyway.

The next group exits, and now it’s our turn to see the real deal. Eddie draws us close.

“These are the mighty Murut hunters,” he says. “They demand respect. Do not flinch or laugh if you want to make it out in one piece.”

“At the entrance,” he continues, “you’ll be greeted by a warrior. Look him in the eye. Tell him your name, where you’re from, and that you’re here to understand more about their culture.”

“I’ll record it for posterity,” Eddie adds.

Groovy.

To John and Denise, I say, “Well duh—we’ve heard the screams. One of those beautiful, copper-skinned specimens is clearly about to scare the bejesus out of us.”

Walking the path, rehearsing my answers, a Murut tribe member leaps from a bush on my right, screaming what I imagine a banshee would scream. Again—no clue what a banshee actually is.

I jump. Christ, you could stand in front of me and say boo and I’d launch.

Reaching the Murut gate, a hot young warrior asks our names and where we’re from. Why do you come here, he asks.

Denise, completely out of turn, puts her arm around me and says:

“I HAVE A BRIDE TO OFFER.”

OMFG. No way. Hahahah—she just said that.

Unrestrained laughter erupts from me. I am completely gobsmacked.

Her timing is flawless. A blow dart, dead center.

For the first time in a very long time, I am the butt of a witty, intelligent, perfectly executed joke

Turns out, ass backward is a direction I follow just fine.

If you enjoyed this, you can buy me a glass of wine. No pressure. No obligation. Just a smile.